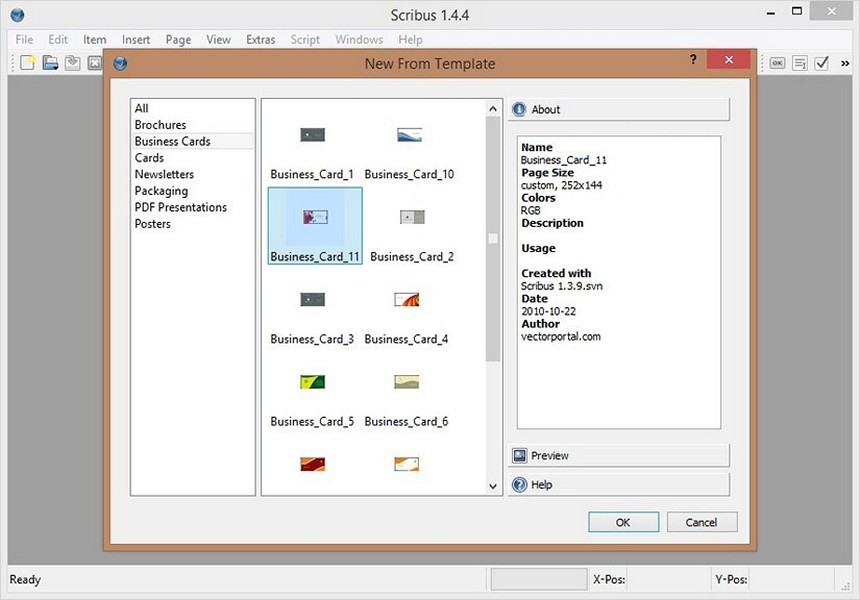

In the Scribus menu, go to File/Preferences. These modifications are described below.įinally, you need to make Scribus use these files. If you are under MacOS X, you will need to slightly modify Scribus to make use of these files. If you are under Windows, they are in C:\Program Files\Gregorio\contrib (assuming you have gregorio installed here). These files are 900_gregorio.xml and gregorio.png. These files are available in the contrib/ directory of the Gregorio sources, and also in the Git repository. There are also some additional files for Scribus which must be installed. For everyone else, check you distribution's documentation to figure out if these packages are installed (and how to make the available if they are not). MiK T eX users should only have a problem if automatic installation of needed packages is disabled. If you used T eX Live, this really should only be an issue if you went for a minimal installation, in which case you'll want to use tlmgr to install them. To be able to use Gregorio in Scribus, you first need to make sure that the extsizes and the filecontents packages are part of the T eX distribution that you installed. It is possible to include Gregorio scores in a Scribus document, and thus to build a book or a booklet containing Gregorian scores simply. Scribus is a free DTP (desktop publishing) software with a simple and accessible graphical user interface. A truly exceptional free publishing tool.This page describes the use of Gregorio within Scribus. Scribus is extremely impressive – its only drawback being limited support for proprietary file types, which is a result of Adobe using licensed technology. You can add your own fonts quickly and easily, and work with scripts using premade scripts to do things like automatically enlarge an object to the full size of a page. Further complexity can be added in the form of layers, with frames set on top of one another, and Scribus also boasts professional publishing elements such as colour separations, CMYK and spot colours. Once you lay all these down, you can then resize or shift things about so everything looks good. Text frames carry your written content, image frames are for pictures, and there are other shape/line frames to make fancy graphics with (graphs and pie charts can be inserted, for example).

You begin with a blank slate of workspace, called the document, and into this you can place objects, the majority of which are frames. It makes sense – Adobe's approach works very well, so why reinvent the wheel? Scribus will take a little whole to master if you've never used a similar program before, but if you're used to InDesign's system of frames and layers, there learning curve is pretty much non-existent.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)